Diagnosis of rarest of porphyria types linked to iron supplement

Woman, 21, found to have CEP after developing liver failure and swelling

Written by |

A 21-year-old woman was diagnosed with congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP) — the rarest of porphyria types — after developing acute liver failure and swelling in the legs and mouth associated with the intake of ferrous sulfate, an iron supplement.

The woman had a previous history of chronic iron deficiency anemia, meaning she had insufficient iron to produce hemoglobin, the protein inside red blood cells responsible for oxygen transport. She also had experienced an adverse reaction to iron supplements as a child.

“This case highlights the importance of having a high clinical suspicion for establishing a diagnosis of CEP,” the researchers wrote, adding that this rare genetic subtype of porphyria “should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with chronic anemia and severe side effects to ferrous sulfate consumption.”

Her case was described in a study titled “Congenital Erythropoietic Porphyria: A Case of Hepatic Failure and Angioedema Following Ferrous Sulfate Supplementation,” published in Pediatric Dermatology.

Woman had chronic iron deficiency anemia

Porphyria is a group of genetic disorders caused by disruptions in the production of heme, a molecule made of iron that helps transport oxygen throughout the body. When this process is impaired, intermediate molecules, called porphyrins, accumulate to toxic levels, causing damage.

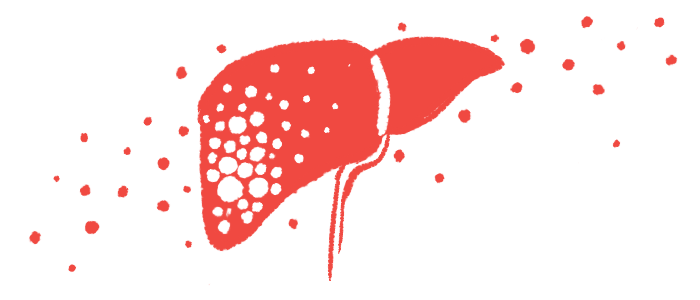

CEP is the rarest of the types of porphyria. It is caused by mutations in the UROS or GATA1 genes, and is marked by severe light sensitivity that leads to scarring and blistering in the skin, and subsequent infections that may lead to the loss of fingers and facial features. Liver involvement has also been reported in people with CEP.

Here, researchers reported the case of a young woman with chronic iron deficiency anemia who was hospitalized with acute liver failure and angioedema — swelling that occurs in the deeper layers of the skin — after taking ferrous sulfate to treat anemia.

At an initial physical examination, she felt generally unwell, and showed signs of scarring in the cheekbones. She also had swelling and skin erosions in the mouth and legs, gum recession in the lower incisor teeth, and severe joint pain.

Blood work revealed the woman had hemolytic anemia, which occurs when red blood cells are destroyed faster than they can be produced, leading to a shortage of red blood cells. She also had low levels of a type of immune cells known as leukocytes, as well as elevated levels of bilirubin and liver enzymes indicative of liver damage.

Her blood and urine levels of uroporphyrins were abnormally high. Upon further questioning, the patient revealed she had an intense reaction to ferrous sulfate during childhood. Based on clinical signs, the patient was diagnosed with CEP. Her family later admitted she had previously been diagnosed with porphyria, but that diagnosis was never revealed to the patient.

The “patient displayed a unique reaction to ferrous sulfate ingestion that has not been reported in existing literature; however, we hypothesize the [disease mechanisms are] related to the accumulation of porphyrins in the liver, which is the primary site of heme synthesis,” the researchers wrote.

Genetic counseling did not ID cause of this rarest of porphyria types

The woman was treated with 1 mg/kg of intravenous, or into-the-vein, methylprednisolone, along with a red blood cell transfusion and vitamin D and E supplements. Wound care was done using disinfectant solutions with antimicrobial effect, topical steroids, and ointments.

After 25 days of hospitalization, her liver enzyme levels significantly dropped, the researchers noted.

The patient was referred for genetic counseling, but the exact CEP-causing mutation was not identified. She also was scheduled for a follow-up with a hematologist and ophthalmologist to manage her anemia and porphyria, and potential eye complications.

For the long term, the patient was advised to maintain a strict diet of 60% carbohydrates, 20% proteins, and 20% fats, and to limit direct exposure to sunlight. She also was advised to avoid iron supplements to prevent further toxic events.

“Our case report emphasizes the importance of physician awareness of CEP since it is a rare disease that tends to mimic other chronic porphyrias, various drug reactions, and collagenopathies [diseases that affect the body’s connective tissue and may lead to the formation of scar tissue],” the researchers wrote.

“It could be advantageous for clinicians to regularly monitor [blood] iron levels in patients with porphyrias to help discern the need for additional clinical management. This could aid in a more detailed understanding and classification of their disease process that may prove to be helpful in future cases,” the team added.