Poorer physical, social quality of life found for EPP children in study

Researchers advocate for children's inclusion in trials for new drugs

Written by |

Children with erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) — who have severe skin hypersensitivity to sunlight — experience “markedly reduced” physical and social quality of life compared with healthy youngsters, and even relative to adults with the condition, according to a study done in the Netherlands and Belgium.

“Ensuring treatment availability for children with EPP is crucial for improving their [quality of life], particularly in terms of social and physical functioning,” the researchers wrote, noting that the pain caused by the condition is “untreatable as it does not respond to analgesics,” or painkillers.

To that end, the team called for new and more studies into treatment options for pediatric patients with EPP.

“We advocate the inclusion of children and teenagers in safety and efficacy studies, for both new and existing drugs for EPP, to ensure availability of treatment in the future,” they wrote.

The researchers noted that symptoms “start from early childhood [and] cause severe pain, which results in lifelong light-avoiding behavior that limits daily and social activities.”

The study, “Quality of life in children with erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case-control study,” was published in The Journal of Dermatology.

Studies done on adults with EPP but data on children are lacking

EPP is a type of porphyria — a group of diseases caused by disruption in the production of heme, a protein involved in oxygen transport throughout the body. The disease is marked by a hypersensitivity of skin to sunlight, due to the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX, a precursor molecule of heme. Light-induced reactions can start at a young age, causing severe pain that is not easily treated.

Several studies have shown poorer quality of life for adults with EPP, but data on children are lacking.

To learn more, the team, led by researchers from the Porphyria Center Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, compared the quality of life of children with EPP to that of healthy children, and further to previously collected data from adults with the disease.

A total of 15 children with EPP and 13 healthy children matched by age, sex, education, and nationality, were included in the study.

Children with the disease also were matched with 15 adults with the condition to assess disease-specific effects on measures of life quality. These matches were done based on sex, age at EPP diagnosis, and disease severity, which was evaluated by measuring the time spent in direct sunlight until the first symptoms appeared.

The median age was 13 for EPP children and 42 for adults. The age at EPP diagnosis was similar — 5 vs. 6 years — between children and adults, and disease severity was not significantly different.

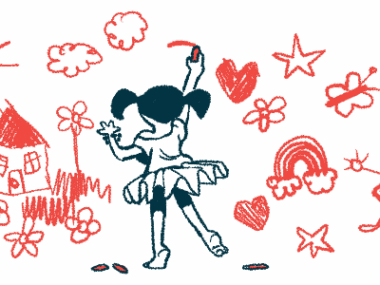

Comparing both groups of children, a higher proportion of those with EPP reported having restrictions at school (46.6% vs. 13% of healthy children), and all children with the disease — versus none of the controls — needed adjustments at school. Also, most children with EPP reported restrictions in career choices (60% vs. 6.7%).

Further, vacations had limitations or restrictions for 93.3% of the EPP children but for none of the youngsters without the disease.

Quality of life worse for EPP children in social, physical domains

The children’s quality of life was assessed through the PedsQL questionnaire, which includes both children’s and parents’ reports covering four domains of quality of life — physical, emotional, social, and school functioning. Children with EPP reported low quality of life in physical function (87.5 vs. 99.2), particularly regarding sports participation, pain, and low energy. However, these differences were not significant in statistical analysis.

Poorer quality of life also was found for EEP children in the social functioning domain (77.5 vs. 97.5), specifically noted in their inability to do things other youth do, or in finding it hard to keep up when playing with others. Scores of school functioning were generally similar to those of healthy children.

EPP children also showed similar disease-specific quality of life relative to that of untreated adults and of treated adults before they were given Scenesse (afamelanotide). Scenesse is approved for adults with EPP in both the U.S. and Europe.

The impact of EPP on the [quality of life] and social engagements of affected children underlines the importance for effective treatment options.

However, when the total EPP score was split into quality of life and disease severity, the children had significantly lower quality of life scores compared with adults (16.7% vs. 33.3%), despite there being no differences seen in disease severity.

Compared with healthy children, those with EPP exhibited significantly higher social inhibition — feeling inhibited, tense, or insecure when with others (66.7% vs. 46.2%). They also had significantly lower scores on a scale of perceived health (80 vs. 91). In contrast, no differences were seen in negative affectivity, or the tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anxiety and irritability.

“Quality of life in children with EPP was especially affected in the social and physical domains. The higher occurrence of social inhibition confirms the suspected impact of disease on social well-being in these children,” the researchers wrote.

“The impact of EPP on the [quality of life] and social engagements of affected children underlines the importance for effective treatment options,” they added.