Drug-eluting stents safely used in man with porphyria, heart disease

Report: Thin tubes slowly release medication inside the coronary arteries

Written by |

A man with genetically confirmed porphyria was treated for blocked heart arteries using stents — thin, mesh-like tubes — that slowly release medication inside the coronary arteries supplying the heart to keep the blood vessels open, according to a report.

The stents, coated with everolimus or sirolimus, two drugs that help prevent artery renarrowing, were chosen even though data on their safety in porphyria are limited. However, both drugs are considered unlikely to trigger porphyria symptoms, and in this case, the treatment was successful without complications.

“These findings, though limited to a single case, suggest that these newer‐generation drug‐eluting therapies may be considered with caution in patients with porphyria when the clinical need outweighs theoretical risks,” researchers wrote.

Their report, “Safety of Everolimus and Sirolimus-Eluting Coronary Devices in a Patient With Porphyria Presenting With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Two-Year Follow-Up,” was published in the journal Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions.

Perphyria symptoms usually appear suddenly

Symptoms of porphyria usually appear suddenly and can include abdominal or body pain, constipation, nausea, and vomiting. Periods when these symptoms occur are called attacks. Treating other health problems in people with porphyria can be challenging because some medications may trigger an attack.

Here, the researchers report on a 59-year-old man who had been diagnosed with porphyria for 20 years. He developed acute coronary syndrome, a serious health problem in which blood flow to the heart is suddenly reduced due to the narrowing or blocking of the coronary arteries, the blood vessels that supply the heart muscle with oxygen-rich blood.

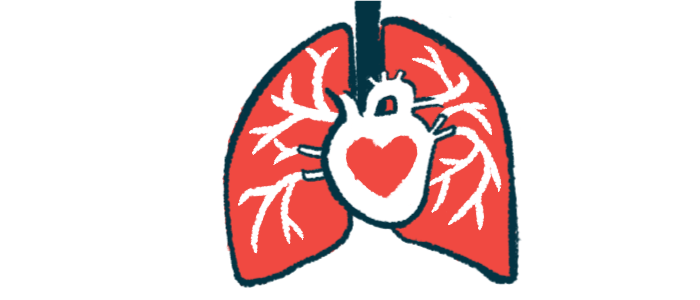

To treat this, the doctors performed a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). This is a minimally invasive procedure where stents are placed inside the narrowed or blocked coronary arteries. Ten years before, he had undergone PCI to place two bare-metal stents in branches of the right coronary artery.

The patient tolerated both interventions well, with only minor, transient cough observed on both occasions and no systemic [whole-body] or cutaneous [skin] signs of porphyria.

The man visited the hospital with worsening chest pain. Tests showed changes in heart beating, but his heart function was normal. An angiogram — a scan that shows how blood flows through blood vessels and possible blockages — found major disease in the mid-left anterior descending coronary artery. Because of his porphyria, the doctors discussed whether drug-eluting stents could be used safely.

The British Porphyria Association was consulted, and it confirmed that both everolimus and sirolimus are considered “probably not porphyrinogenic,” the researchers wrote, adding that “the patient was informed of the residual risks and consented to PCI.”

An everolimus‑eluting stent, called SYNERGY, was placed in the blocked coronary artery. Everolimus works by slowing the growth of scar tissue, preventing the blood vessel from narrowing again. Immediately after, the man had a brief dry cough that quickly resolved. He was discharged the same day and remained symptom-free for two years.

When chest pain returned, the man underwent another PCI. This time, the doctors used a different everolimus-releasing stent called Xience, which they overlapped with the previous one. They also placed a balloon coated with another medication, sirolimus, to treat a completely blocked, smaller branch of the coronary artery. Sirolimus works in a way similar to everolimus.

This case is relevant because there were no porphyria-related complications from the use of everolimus or sirolimus.

“The patient tolerated both interventions well, with only minor, transient cough observed on both occasions and no systemic [whole-body] or cutaneous [skin] signs of porphyria,” the researchers wrote.