HMBS Lack Seen to Affect Mitochondria, Cause Depression in AIP Mouse Model

Severe lack of hydroxymethylbilane synthase (HMBS) — the defective enzyme in people with acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) — led to abnormalities in mitochondria essential for cellular energy, and to depression-like symptoms in a mouse model of the disease, a study reports.

The study, “Severe hydroxymethylbilane synthase deficiency causes depression-like behavior and mitochondrial dysfunction in a mouse model of homozygous dominant acute intermittent porphyria,” was published in the journal Acta Neuropathologica Communications.

AIP, the most common and severe form of acute porphyria, is caused by mutations in the HMBS gene, which are thought to lower the activity of the resulting HMBS enzyme by 50%. This enzyme is required for the production of heme, a molecule essential for the transport of oxygen in red blood cells, and the breakdown of compounds in the liver.

A mouse model with HMBS activity at nearly 30% of normal has been useful in studying disease mechanisms of AIP, and in exploring potential therapeutic approaches. However, these animals only start showing the typical clinical and biochemical manifestations of the disease after being treated with phenobarbital, a sedative normally used to treat seizures in people. For such reason, behavioral tests are greatly limited in this model.

More recently, a different mouse model that retained only 5% of HMBS activity was created to mimic a rare subtype of AIP caused by dominant mutations in the HMBS gene. (Dominant mutations can cause a specific trait or disease when present in a single copy of the two gene copies each person inherits.)

Unlike the previous model, these animals do not require pre-treatment to develop AIP symptoms, and so might be useful when investigating behavioral features and underlying molecular mechanisms of the disease.

Investigators at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, in collaboration with colleagues at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, used a battery of tests to analyze behavior in this recent mouse model of AIP.

They also used techniques to pinpoint which genes and cell components could be involved in disease development.

Behavioral tests revealed that mice lacking HMBS activity showed signs of depression, which could be alleviated by treatment with escitalopram, an antidepressant that belongs to the group of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Transcriptomic analyses and visual examination of animal brain samples found a lack of myelination — the process by which myelin, the fatty substance that protects nerve fibers, is deposited around nerve segments — accompanied by a reduction in the number of oligodendrocytes, the cells that produce myelin.

Of note, transcriptomics is the study of all RNA molecules in a cell that are used as template for the production of proteins.

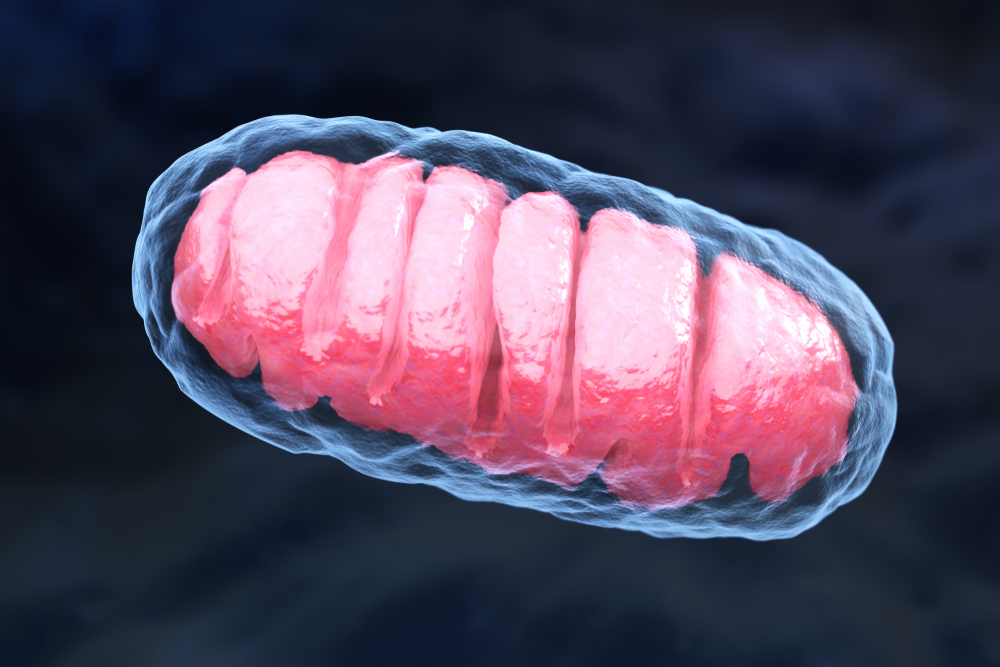

The investigators also isolated mitochondria — cell compartments responsible for the production of energy — from the animals’ hippocampus, a brain region involved in short-term memory and learning.

In these mitochondria, they found two protein complexes (complex III and complex IV) that are part of the respiratory chain — the signaling cascade mitochondria use to produce energy — with lower than usual activity, which led to problems in the mitochondria.

“This study for the first time reveals the behavioral consequences of severe HMBS deficiency in a mouse model of … AIP and proposes mitochondrial dysfunction as relevant pathophysiological [disease] mechanism,” the researchers concluded.