Workup Before Stem Cell Transplant in CEP Patients Should Include Liver Assessment, Study Says

Written by |

Patients with congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP) should have a liver biopsy to assess the degree of liver damage before undergoing a bone marrow transplant, a study suggests.

The study, “Bone Marrow Transplantation in Congenital Erythropoietic Porphyria: Sustained Efficacy but Unexpected Liver Dysfunction,” was published in the journal Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Patients with CEP experience severe skin sensitivity to sunlight.

In CEP, chronic hemolysis, or destruction of red blood cells, results from defects in an enzyme called uroporphyrinogen-III-synthase (UROS). This enzyme is required for the production of heme, a molecule essential for red blood cells to transport oxygen, and for the breakdown of compounds in the liver.

To date, a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is the only therapy with the potential to restore the production of functional UROS and cure CEP. This technique is based on the transplant of hematopoietic stem cells — cells that can give rise to all types of blood cells in the body — from a genetically similar donor, usually a close relative of the patient.

Since 1991, more than 20 cases of CEP patients receiving HSCT have been reported in the literature.

“Independently of the tolerance of the transplant procedure itself, HSCT for the treatment of congenital diseases requires a detailed description of the disease evolution, as some symptoms may not be improved, or only partially, by the supply of an enzyme via hematopoietic cells,” the researchers wrote. “Certain symptoms, unknown during the natural course of the disease, can appear in the long term through the prolongation of the lifespan of transplanted patients.”

They described the cases of six children with CEP who underwent HSCT between 1994 and 2016 at the Pediatric Immuno-Hematology and Rheumatology Unit of Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital in Paris.

Three patients underwent the transplant procedure a second time after the first HSCT failed. Two of the six were the very first patients to have the procedure more than 20 years ago.

Four of the patients are currently leading a nearly normal life six to 25 years after receiving the transplant. None of them experienced any skin or blood manifestations of CEP since the procedure, and all have nearly normal heme metabolism values.

Two patients died in the first year following the transplant: one from unexplained acute liver failure, and the other from severe graft-versus-host disease, a potential life-threatening condition that occurs when the recipient’s immune system recognizes the donor’s cells as a threat.

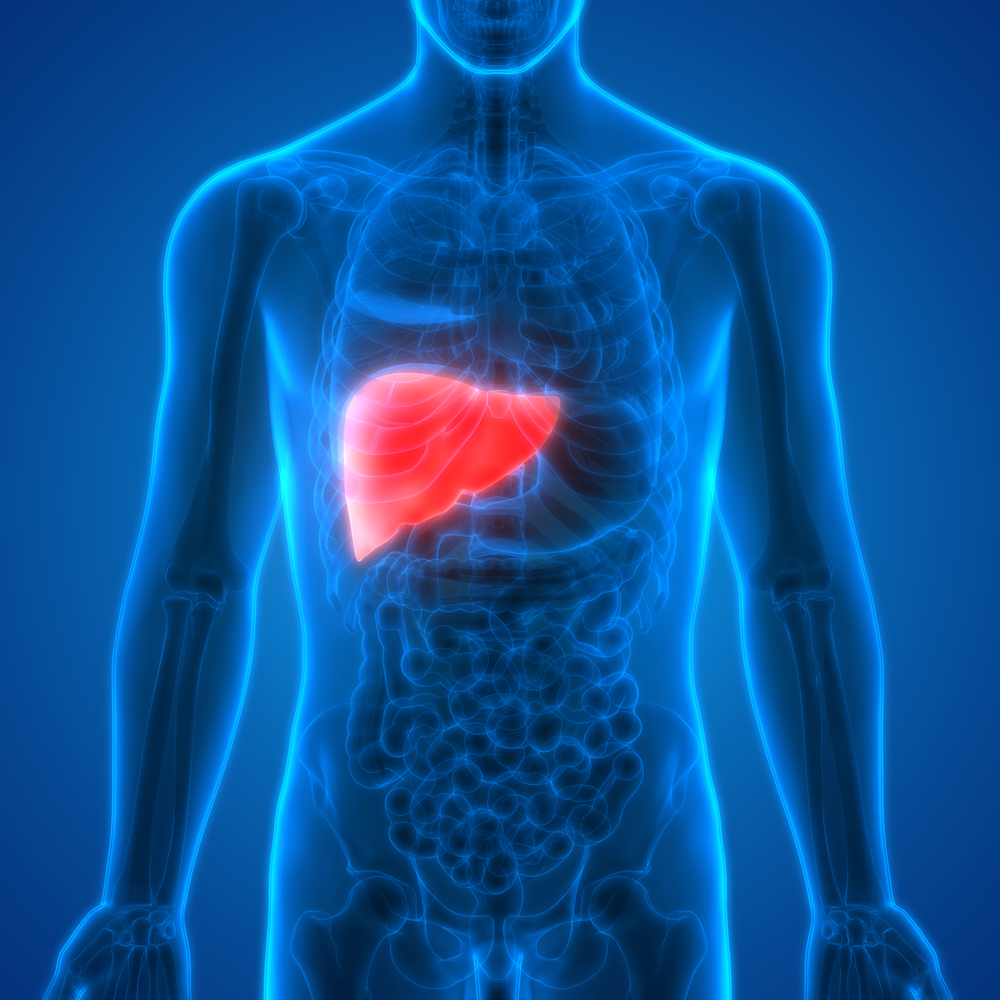

With the exception of the child who died from liver failure, liver function assessment values gradually returned to normal in the remaining five children following the transplant.

Liver biopsy findings revealed that before undergoing a bone marrow transplant, half of the children showed signs of liver damage, including tissue scarring (fibrosis) and a high number of porphyrin deposits (up to 60 times higher than normal), of varying degrees of severity. Of note, porphyrins are byproducts of heme metabolism.

“Despite difficult engraftment, the long-term efficacy of HSCT in CEP appears to be favorable and reinforces its benefits for the severe form of CEP,” the researchers wrote.

“[W]e strongly suggest that the initial workup before HSCT includes a liver biopsy to evaluate the level of liver damage and the level of porphyrin accumulation,” they added.